Oz : Brief Transformation

To Design Brief is to Design the Project

by PAVA

Published on OZ Volume 47, 2025, College of Architecture, Planning and Design, Kansas State University

Editor : Kylee O’Dell and Matthew Murphy

Faculty Advisor : Christopher Fein and Michael Grogan

From our journey of design education and architectural practice in Thailand, the architectural project brief is often written by a privileged group of people resulting in one way communication and a top-down approach. The design brief in Thailand appears to represent a sense of strong vertical social structure and hierarchy which was deeply rooted in Thai history socially and politically. Following the western industrialization and globalization, the need for complex as well as public building typology in Thailand was an urgent issue in the past century. Instead of the traditional craftsman, “Architect” is from a westernized vocabulary and new profession, interestingly proven and adapted to Thai social class, political structure, and economic landscape. One of the major factors for which the profession was successfully established are the reasons for durable and practical uses, and dealing with complex tasks. In many cases of the beginning of architecture school establishment, students need to logically follow the design brief, which has clear and rigid deliverables of practical building type and usable building scale. With good intentions in the academic world, a “made to order brief” has trained students to be an architect to serve globalization as the foundation of the nation. From our observation, it is true that the training brief gives students a pragmatic foundation, which is crucial to being an architect, such as excellent drafting and visualization skills. However, the traditional training briefs appear to significantly influence a designer's linear thinking process. They often demand a clear, quantitative program from the client, generally resulting in various types of market-driven briefs. Rather than the conventional approach or top-down command, we believe that the design brief needs to be holistically designed from the ground-up as the first critical stepping stone to make a positive change and impact to the project outcome.

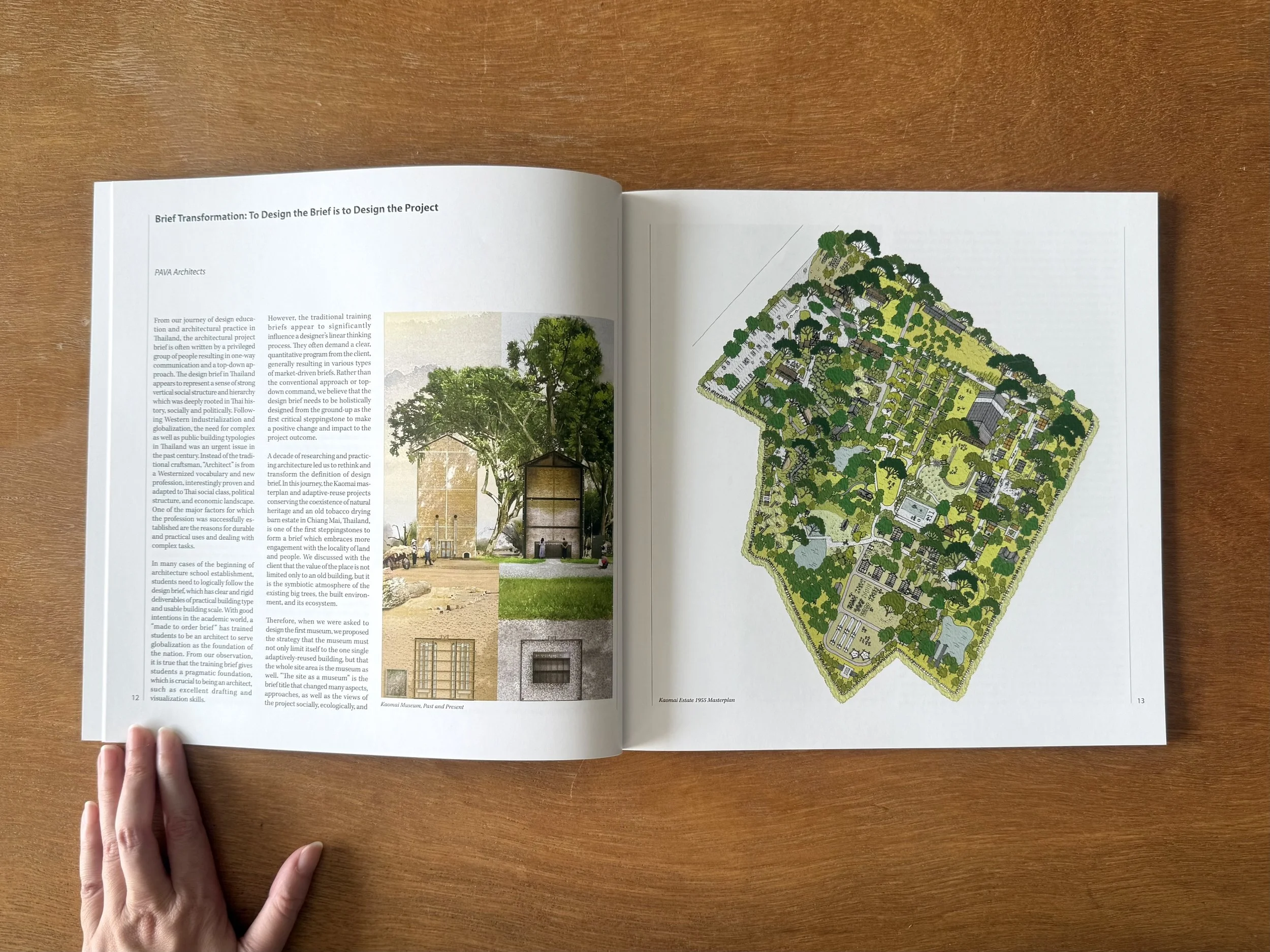

A decade of researching and practicing architecture led us to rethink and transform the definition of design brief. In this journey, the Kaomai masterplan and adaptive-reuse projects, conserving the coexistence of natural heritage and an old tobacco drying barn estate in Chiang Mai, Thailand, is one of the first stepping stones to form a brief which embraces more engagement with the locality of land and people. We discussed with the client that the value of the place is not limited only to an old building, but it is the symbiotic atmosphere of the existing big trees, the built environment, and its ecosystem. Therefore, when we were asked to design the first museum, we proposed the strategy that the museum must not only limit itself to the one single adaptively-reused building, but that the whole site area is the museum as well. “The site as a museum” is the brief title that changed many aspects, approaches, as well as the views of the project socially, ecologically, and educationally. This brief is not a single week of effort, but it takes time to collect valuable information from locals, ex-workers, and families of the estate founders; do several surveys onsite; collaborate with botanists, conservation specialists, arborists, engineers, and local artisans. Again, we do believe that the brief could be designed, which significantly changes the project outcome and has a more positive impact. What the brief “does,” could be meaningful and gives hope for the future.

During the Covid pandemic years, we initiated the Re-Balcony research project, observing the balcony uses and adaptability in Din Dang, Huai Kwang, and Klong Toei Areas. The project was researched from our collections of fieldwork photos in low-income zones and affordable housing areas of Bangkok. Balconies often function as an extra free space for engaging with urban fabric, gaining fresh air and natural light, and miscellaneous utilitarian uses—drying clothes, planting trees, cooking meals, washing dishes, and hanging air-conditioner condensing units. These balconies have been adapted to fit the users’ needs. With the affordable intervention framework of “reorganizing, removing, and adding to” existing balcony conditions, we found alternative design solutions to enhance inhabitants’ well-being. The “users’ self-intervention” could range from easily cleaning and adding some temporal device to the small addition of shading devices and structures responding to the climate and privacy. Interestingly, the modernism of rigid housing briefs has been organically changed by a local dweller in response to the uses in the tropical climate with limited resources. Perhaps, the aesthetic of the architecture is the life which gives a new rhythm to the uniformity of the building. From our research and observation, the dwellers themselves can even write their own briefs. Affordable housing needs to allow self-incremental intervention within the organized framework to be more open-ended and encourage the users' needs and change.

Embracing changes is always the key of our design strategy, especially in urban contexts that rapidly change over time. In 2019, we built the Care Station project in collaboration with Carenation and Refill Station, a platform of good act socially and environmentally. Starting with the intention to help the underprivileged, create jobs, and encourage eco-friendly living, the team shaped the brief together and posted the question to society that, "If you were to die tomorrow, what would be the legacy you leave behind?" We searched for a physical space to test our belief and found a tiny vacant space amidst turbulent urban life transiting on the Skytrain platform and connecting to one of the significant Buddhist temples in Bangkok. Care Station is designed to minimize all of the construction materials in all details—only small modular plywood shelves and solid timber joints, responding to the belief of minimizing what we leave behind. This basic system establishes “a simple, flexible, and reusable module,” allowing to reorient, adapt, and change over time. The design is open-ended, serving not only refill product, funeral wreath, and donation activities, but also acting as an open-stage node that could be reconfigured, responding to the rapid changes. Together, the brief creates not just a space but the system as a social infrastructure.

In 2020, PAVA was invited to participate in a hospital's new proposal in Bangkok. With the purpose to modernize the hospital, the initial brief was to re-facade the main building of the hospital by wrapping the existing building with a full-height glass curtain wall system. Ironically, the hospital aspired to change the building appearance to be more “modern” by the post-modern symbolic facade approach. On the day we proposed the project, instead of following the modernized brief, we proposed to have months of on-site fieldwork, research with a series of holistic engagement of doctors, medical staff, and patients. It was a meaningful month—we spent time together with users, not only the medical staff but also the gardening and building maintenance team. Rather than modernizing objects, we humanized the project. At the end of the research period, we designed and develop the brief with the hospital board, together with users, to have an “incremental design strategy brief” consisting of a short-term plan and a long-term plan. For the short-term plan, we proposed the adaptive reuse of abandoned spaces in existing areas to serve immediate needs such as a healing garden, recreational space, and food and beverage programs as the quick-fix approach. On the other hand, for the long-term plan, the green link, medical and social facility, water management element, and utility infrastructure are all incorporated as the main bridge embracing the continuous changes of the hospital. This new connectivity will holistically link all of the complex medical programs together in the future. We learned so much from this process of collectively making a brief, which teaches us that designers have the power to contribute, not only to the project, but also to the community and the environment.

In the decade of our practice, some briefs required designers to create a “White Box” in order to gain a modernized and westernized symbol. Concrete and paint are favorable because people have a feeling that it is cleaner and lasts longer with a minimum of maintenance issues. Devaluing the timber house, some locals move to live in concrete house with a metallic roof, especially the blue metallic roof representing the wealthy status of their family. Because of Thai industrialization, bad practices in timber harvesting, as well as the promotion of agricultural and industrial zones, significantly limit the natural forest area and wood supply. At this point, the popularity of the modernized industrial materials, combined with the limitation of natural resources, has pushed timber as an alternative building materiality in the Thai design industry. From 2017-2025, we had a chance to develop a brief with the clients to design a timber house and a timber hotel next to the Mekong River. We tried to understand the limitations of the timber resources and craftsmanship skills. Realizing the key of the brief is not, “the bigger building is the better building,” but it is much more about the appropriate scale that represents the value of timber, land, and the river. Not driven by the capital and market, we limited the area of building footprints and the number of the rooms as well as not creating too much of a burden for the maintenance of the project in the long run. Trying to understand the local craftsman skills and the availability of resources, such as local carpentry skills, local handmade brick, or local fabric around the site is also the key factor of the brief. Collecting and reusing timbers from various old houses, warehouses, and rice mill factories as the main project material and structure was the purpose of the brief, illustrating the imperfect aesthetic of the timber. We believe that timber should not be a limited resource providing only for small groups of people. Ideally, the brief suggested that timber should be more appreciated and more affordable in general, especially in the tropics where trees grow rapidly thanks to the rich water and soil.

In this world full of change and uncertainty, we hope to see the architect with more engagement and brave enough to ask questions about the design brief. We understand that a clear brief will lead to a firm architect’s foundation, however, we believe that the holistic integration of the “made to order brief” with the “together-made brief” will pave the way to a constructive and productive result. With hope, we believe multi-way communication embracing the diversity of thoughts will be one of the critical keys opening to positive opportunity. Again, the design brief is the critical first steppingstone leading the way to a more holistic design approach, which not only focuses on the financial layer, but needs to embrace the social and ecological layers. Not only proposing clear-cut architectural programs—such as 500 rooms for a luxurious hotel, or a new curtain-wall facade— the brief needs to be open-ended and engage with the specificity of the context and people. Perhaps, the design school may not limit the brief only to a single modern building typology, but also provide a chance for students to explore their own multiple briefs. Only one single building type. or the idea of “one size fits all,” may not fulfill the need of this global phenomena of rapid urbanization and climate change. Not only closed-end pragmatic design approaches, we also wish to see architectural students have more freedom of constructive thoughts. In practice, the design brief should not only be written in the board meeting room following the market, but it also can be engaged everywhere with everyone. Architectural practice should be a process that helps flattens the vertical social structure as a tool that bridges peoples’ hearts and souls together. The brief is a process, not an end-result. To design the brief is to design a much more meaningful opportunity and positive impact of the project.